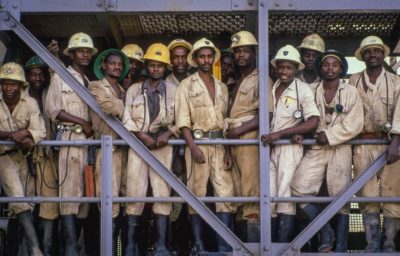

The southern African nation of Zambia is home to a wealth of minerals — in particular, lots of the copper and cobalt that the world will require to power a green economy. Among its largest operations is the Konkola Copper Mines (KCM), located in the country’s Copperbelt Province. In 2004, U.K.-based Vedanta Resources acquired the controlling stake in KCM, whose operations span 11 square miles along the Kafue River. Soon after, residents noticed that the Kafue was emitting foul odors. Fish began dying. Crops began to wither. Livestock fell ill. And villagers came down with mysterious headaches, nose bleeds, rashes, and burns.

Chilekwa Mumba, who had grown up in the region but since moved to the Zambian capital, Lusaka, learned of the problem and vowed to do something about it. In an interview with Yale Environment 360, he talks about how he spent the next several years facilitating meetings between the communities and British lawyers, gathering water samples, and convincing former mine workers to provide evidence for a lawsuit that made its way through the British court system. Finally, in 2019, its Supreme Court found that KCM’s parent company could be held accountable in the U.K. for environmental damage from the mine’s operations.

Not only had Mumba, 38, who was awarded a Goldman Environmental Prize two weeks ago, helped win significant financial compensation for the 2,000 villagers involved, but his case set a legal precedent that British companies can be held accountable for the environmental fallout of their operations overseas. In 2021, a group of Niger Delta residents sued Shell Global in the U.K. for years of oil spills that had contaminated their land and water, after the Supreme Court rejected Shell’s arguments that its Nigerian subsidiary held liability.

“It was just me trying to do the right thing,” Mumba says of his efforts. “The ripple effect has been amazing.”

Yale Environment 360: KCM was already a presence when you were growing up in the town of Chingola. In fact, your father worked for them. How did you feel about the mine back then?

Chilekwa Mumba: It was a positive thing, because it was being run as a parastatal, under the state, when Zambia was under a very different system of economic management. We had socialist leanings at the time, so the mine’s [corporate social responsibility] was very elevated.

e360: You did your primary schooling in Chingola, so you got a good education in part thanks to the mine, which funded the schools?

Mumba: Not in part, completely — especially from grade one to grade 12. They had excellent schools. We moved to Lusaka when I was 15, but I still went to school under the mine system. I went to a boarding school that was supported by the mines, including KCM.

e360: In 2004, Vedanta Resources, which is headquartered in the U.K., acquired a controlling stake in KCM. What happened after that?

Mumba: When they took over, there was too much collusion with government. They were not being held to account on many different issues. Based on what I was reading in the media, I started talking to residents in Chingola. We’ve got family and friends there, and my parents still maintain a home there. I used to go back occasionally, but it became almost a permanent home when I started to find out about the reports [of pollution]. I began realizing that what I’d been hearing was correct. And I started to do my own investigation.

“I went there myself and found there were basically no fish [in the river], and the smell of chemicals was quite evident.”

e360: What did you find?

Mumba: I went to the same spot I used to go to as a child to fish. Even if it was now full of bush, I somehow made my way there, because I could remember it from childhood. I was being told, “You will not catch a single fish from that point because it’s polluted.” But I went there myself and found that, yeah, there were basically no fish, and the smell of chemicals was quite evident. The soil makeup was different from what I remembered when I was young.

e360: Did you confront the company?

Mumba: I knew it would be a brick wall, because I knew that efforts had been made within our local judiciary and nothing had happened. So I said, “We have to find alternative means to deal with this issue.” I had a couple of meetings with a local lawyer representing the villagers, and he was telling me that nothing would happen, that I shouldn’t waste my time. But he did give me quite a bit of information, and I put it in my file.

e360: You wrote letters to something like 100 law firms?

Mumba: A combination of law firms and environmental NGOs, all over the world. I was just randomly sending them out from my Yahoo address. I got a lot of automatic replies. And then there was an automatic reply from [British law firm] Leigh Day, followed up with an actual email from a person, Katie Gonzalez. I can never forget that name. I happened to find it in my email and was surprised. They told me they would be there in two weeks.

e360: How did the community respond to this British lawyer coming in? Did they trust him?

Mumba: Not immediately. But the way he is — Oliver Holland, I have to absolutely mention him — he was a white guy in a remote village, but he has this aura about him where he is very friendly, so they warmed up to him.

e360: What sort of evidence did you bring to court?

Mumba: We gathered water samples and soil samples and found that copper, iron, cobalt, and dissolved sulfates were present far beyond legal limits. We also took in — though we did not put that to the court — blood tests for various clients, to test for the presence of heavy metals. We already had overwhelming evidence from the water and the soil.

e360: Did you have help from anybody inside the company?

Mumba: A former mine manager, who knew the whole process and how there was gross negligence on the part of pollution control, gave us a lot of documents. He, of course, did not want to be named, so we videoed his testimony using certain means where his identity could be withheld. Somebody else who worked for the company had a lot of information garnered from ex- and current employees.

e360: They also lived in the area and were concerned about their families?

Mumba: They did not live in those particular villages, but they are part of Chingola town. And they also had concerns. Because of my connection to the case, I would get random calls and they would say, “Can we meet you? We want to help you. But protect our identity.” So I would meet as many as possible. I would talk to everyone. It was part of the investigation, to get all that evidence together.

e360: You studied management information systems at university, but now you were learning to be both a community activist and an investigator?

Mumba: Yes, quite by accident. Because at the time, funnily enough, I was working for a local law firm, as a business development consultant. But I abandoned that work and decided to do this. I honestly didn’t even think that I was doing an investigation per se. It all came together when I was just simply inquiring into all these issues. And as I was working with Leigh Day, they would ask, “Do you think you’re able to get this information?” And I would say, “Yeah, yeah. Let’s see who I can talk to and pick it up from there.”

“The villagers were ecstatic [about the court ruling]. It had been a long journey, and so it was a very, very joyous moment for them.”

e360: Was it scary, talking to people and not being sure if they were working for the company? Did you face harassment?

Mumba: I used to ignore those negative aspects. It’s after the fact that I’ve thought about the risk. Because I didn’t feel intimidated, despite the warnings I would get even from family. They were like, “What you’re doing, you’re risking yourself, your life.” I just felt something had to be done about the issue. So it’s after all this has happened that I said, “Oh, I really shouldn’t have done this.” We did a lot of crazy stuff. We trespassed into the mine at one time with a lab technician. I had to lie to security. There was a whole lot of stuff that I did when I look back, I’m like, “Huh, maybe I should have taken more care.”

e360: Weren’t you arrested at one point?

Mumba: We were meeting with our clients, and the police came in with their mine vehicles and their police vehicles, quite a squadron of them. And they picked us up saying, “You’re not supposed to be here. You’re having an illegal meeting. You’re meeting too many people at the same time.” We have a funny law code, the Public Order Act, which is only enforced at the convenience of political interests or police interests. So yeah, they took advantage of that, and I got arrested. I just said, “Well, if they arrest us, that’s part of the whole thing,” despite the very unpleasant experience in the police cells.

They kept us for about eight hours. But they were in such a hurry to get us into the cells that they forgot to relieve us of one of our phones. So we took advantage. We took pictures of ourselves in the cells. We shared them with the law firm and our Zambian team. We were talking to them just direct on the phone, and then if we heard the wardens coming, we’d hang up.

e360: This case went on for a period of six years. Had it basically become your full-time job?

Mumba: Yes. And I’m still working with Leigh Day on a number of issues. It’s basically my full-time job.

e360: Where were you when you got the news that you had won on appeal?

Mumba: I was in Chingola at the time. Oliver called me. The villagers were ecstatic. They were dancing and everything. It had been a long journey, so it was a very, very joyous, momentous occasion for them.

e360: What exactly was the settlement?

Mumba: The villagers were given monetary compensation. And I will add that in the course of those six years, offers had been made to them, both formally and informally. And this is a very impoverished community, so we had to do a lot of firefighting, because we were like, “That’s not enough money to sort out this issue.” And, of course, there was always a group who said, “We’re tired of waiting. We’re just going to accept this offer soon.” So that final offer, we thought it was something which was at least sensible given the situation.

e360: And is the region now all cleaned up? Can you go back and find fish in the river?

Mumba: No, it’s not. That’s a whole different issue. And Vedanta is no longer running the mine; the government is running the mine. What has ended up happening is a whole other sad story, because the government is policing itself, and the government is not holding itself accountable.

“There’s now a very easy excuse: ‘We’re doing this for clean energy.’ And that excuse can blind a lot of people.”

e360: We know that copper and cobalt will be critical to the new green economy. Lots of people, including in the United States, want Zambia’s minerals. How does that help or hinder your position?

Mumba: I see it as a very dangerous position, especially the thirst for cobalt. I feel like the communities around the mines have never gotten a fair share of the deal. America says the end game of mining is they want clean energy. Cobalt is one of the components for that. So right now we need to be more watchful about how these mining operations are taking place and what benefit goes to the community.

I’m not talking about “trickling down” — the community needs to get a benefit. And I’m not talking about employment. They have to do more. I’m actually watching that company, KoBold Metals [a startup backed by a group including Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos that is developing a copper-cobalt mine in Zambia], and I’m trying to find out more about its modus operandi. But I feel we need to be more vigilant now because there’s a very easy excuse: “We’re doing this for clean energy.” And that excuse can blind a lot of people.

e360: This case has set a precedent when it comes to the exposure of companies whose subsidiaries are implicated in environmental and other offenses. It was your work that enabled villagers in Nigeria to successfully sue Shell oil after decades of wrongdoing.

Mumba: What can I say? You take one little step and you don’t know the impact it has.

Source : Yale